Every year approximately 1.3 million women and 835,000 men are physically assaulted by their partners.

Other striking statistics include:

- Out of all women murdered in the US each year, 40-50% were murdered by their intimate partners. In 70-80% of the homicides that occurred during incidents of domestic violence, no matter which partner was killed, the man physically abused the woman before the murder.

- Sexual assault or forced sex occurs in approximately 40-45% of the relationships where there is domestic abuse.

- 93% of women murdered by men in single-victim incidents were killed by husbands, exes, boyfriends, aspiring boyfriends, family members, friends and colleagues.

- 25% of women and 7.6% of men, aged 18 or over, experience domestic abuse during their lifetime.

Many of these crimes are preventable due to such cases usually being preceded by several warning signs. It is therefore very clear that current and evolving technology has a significant role to play in helping law enforcement reduce these worrying numbers.

GPS Tracking

Domestic violence carries a high rate of repeat offenders and, even though protection from abuse orders are a common remedy, no contact provisions can be difficult to enforce because the abuser is usually intimately familiar with the routine of the survivor.

GPS technology has been proven time and time again to strengthen the effect restraining orders; reportedly showing that violent offenders are, overall, 95% less likely to commit a new crime.

Past and current trials include:

- In 2010, Connecticut began monitoring 168 high-risk domestic violence offenders: None of the victims were re-injured.

- In Massachusetts, the Domestic Violence High-Risk Team has monitored 172 high-risk cases since 2005: Men tracked by GPS did not commit further violence.

- The New Jersey State Parole Board has stated that the re-offence rate of sex offenders being tracked by GPS dropped from 5.3% to 0.4%.

- Since 2018, Tasmanian and Federal government departments in Australia have attributed AUD $2.5m to an 18-month trial on those suspected of serious or repeated family violence

- This year, the state of Western Australia (WA) has budgeted AUD $15.5m and 10 new police officers towards a 24-hour unit to monitor family violence offenders who have breached violence restraining orders (VROs). Women’s Council Chief Executive, Angela Hartwig, said: ““I think what we find with breaches of restraining orders is often they might not be taken seriously, and when we’re talking about this electronic monitoring we’re talking about the high-risk offenders…The ones that could make or break a domestic homicide situation. The ones we know disregard the law and often disregard a VRO and there could be fatal consequences. These things could save lives and we know they have.”

GPS-tracking of domestic violence offenders functions by the victim deciding to carry a device that notifies them once the offender comes within a certain proximity of their location. The victim can decide whether to select only ‘stationary’ locations (such as their home, office etc) or also include their mobile locations.

If the offender violates their restraining order, trained operators notify both the victim and local police officers. The victim is guided to a safe location, away from the GPS-tracker of offender, who can then be held accountable for their violation.

However, it is important to note that this technology also has its failures, meaning that its use should potentially be considered only for repeat or serious offenders.

Virtual Reality

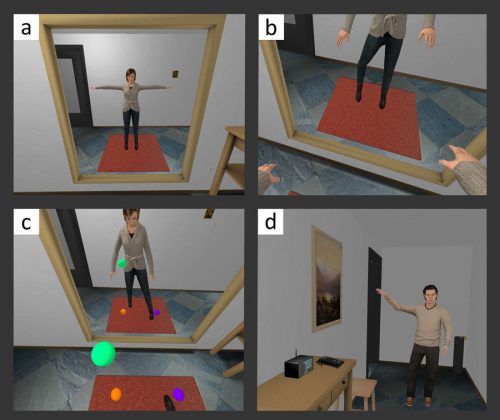

The role of empathy and taking the victim’s perspective has been highlighted in several theoretical models for preventing future aggressive behaviors. After successful tests by researchers at the University of Barcelona and the government of Catalonia, Virtual Reality (VR) technology is set to be trialed in the UK to help tackle the issue of domestic violence.

Using the VR headsets, the male offenders were transformed into women and were able to experience being on the receiving end of domestic violence. The test subjects (who are the victims in this scenario) are confronted by a digital aggressor, who shouts verbal abuse while moving closer to them. The system, which uses artificial intelligence as well, can detect if the subject tries to disengage from the aggressor by not looking at it. If the ‘victim’ looks away from the aggressor, they experience further threatening behavior such as being shouted at to look back towards the aggressor.

Mel Slater, the co-author of the study, said: “The atmosphere is interactive since the abuser looks at the participant’s face and shouts ‘shut up!’ When speaking, or ‘look at me!’ If looking elsewhere.”

The product is named ‘VRespect.Me’ and is manufactured by Virtual Bodyworks, who state on their website, “VRespect.Me is a powerful virtual reality experience designed to rehabilitate men with a history of domestic violence. It is the only scientifically proven product of its kind in the market.”

Police Body Cameras

Due to the nature of the relationship between attacker and victim, domestic violence calls can be some of the most difficult to prosecute. The victim very often recants their official statements or refuses to cooperate with law enforcement after the initial call.

In these cases, according to the NYPD, body cams have become an invaluable tool: “When an officer is responding to a 911 call and that victim is trembling and their voice is cracking or you might see them with an injury, to capture all of that on video is tremendous,” Deputy Chief Martin Morales explained. “If an offender is on the scene, they might make statements like, ‘Yes, I hit her’ and we get a confession on video. That all builds a strong case.”

Stuart Lister, from the University of Leeds Centre for Criminal Justice Studies in the UK, who led research on how the new technology was being used by police forces in West Yorkshire and Cumbria, said: “Officers told us that the videos had the potential to provide a more powerful picture about the impact of domestic abuse on victims, footage would show if people had been injured, were distressed or if the home had been damaged.”

One officer told the researchers: “I’ve seen a really good example of where a guy threw a bottle at his girlfriend and it slashed all the way down the back of her calf muscle and the paramedics were still there treating her, so it was an open, gaping wound. You can see the severity of the wound…The body-worn cameras can capture evidence that could be lost or diminished.”

West Yorkshire Police has invested in 2,300 of the cameras, which are worn on police uniforms, and their use is now mandatory for all officers responding to domestic violence calls. The video doesn’t lie, and that makes it great for providing nearly irrefutable evidence.

Polygraph Tests

(Image source: flickr.com/photos/144715760@N08)

The draft of the Domestic Violence Bill in the UK was released earlier this year, with one of the main proposals including the use of polygraph testing of domestic violence offenders on conditional release from prison.

The proposed polygraph tests would be used to help determine the risk of an offender released into the community, or more specifically, their compliance with conditions of release and to improve the management of offenders when released.

The polygraph test is part of a broad package of measures, which also incorporates a ban on the cross-examination of victims by their abusers in family courts. Other measures include the introduction of domestic abuse protection orders (placing restrictions on offenders) and the introduction of the first-ever statutory government definition of domestic abuse to specifically include economic, “controlling and manipulative non-physical abuse.”