Modern police equipment is hugely varied, spanning from the simple baton all the way to high-tech body cameras and radar guns. But how much do you know about where they came from?

While we rarely think of the origins of these items, each one has its own history. Some were developed by civilians, some by the military and others by corporations. Some were invented for the same use they have today, while others were created for a completely different purpose and were later adapted for police use. Here are five everyday pieces of police equipment and their surprising backstories.

TASER

The TASER has become a staple non-lethal weapon of modern police. Although some countries have banned or restricted their ownership, they are widely available in the USA. TASERs are not considered firearms under US law, meaning that they are legal for police use in all 50 states and legal for citizen ownership in 48 (ownership is currently restricted in Hawaii and Rhode Island).

The TASER was developed in the USA by a NASA researcher named Jack Cover who started work on the device in 1969, producing a working model five years later in 1974. Jack Cover’s childhood hero was a fictional inventor named Tom Swift, so he named his invention the Tom A. Swift Electric Rifle, or TASER for short. The original model used gunpowder to project its electrode darts, which means it was originally classified in the USA as a firearm. However, the company quickly remodeled the device to use small nitrogen gas canisters as propellants, which is why the TASER is no longer considered to be a firearm.

TASER is technically a brand name owned by Taser International. Any similar product made by another company should be referred to by the generic name of ‘stun gun’ or ‘conducted electrical weapon’ (CEW). A 2011 report by the National Institute of Justice showed that 15,000 police departments and military agencies use TASERs in the USA alone. Internationally the TASER has been adopted by some countries but not others; in the UK, police have had access to them since 2003.

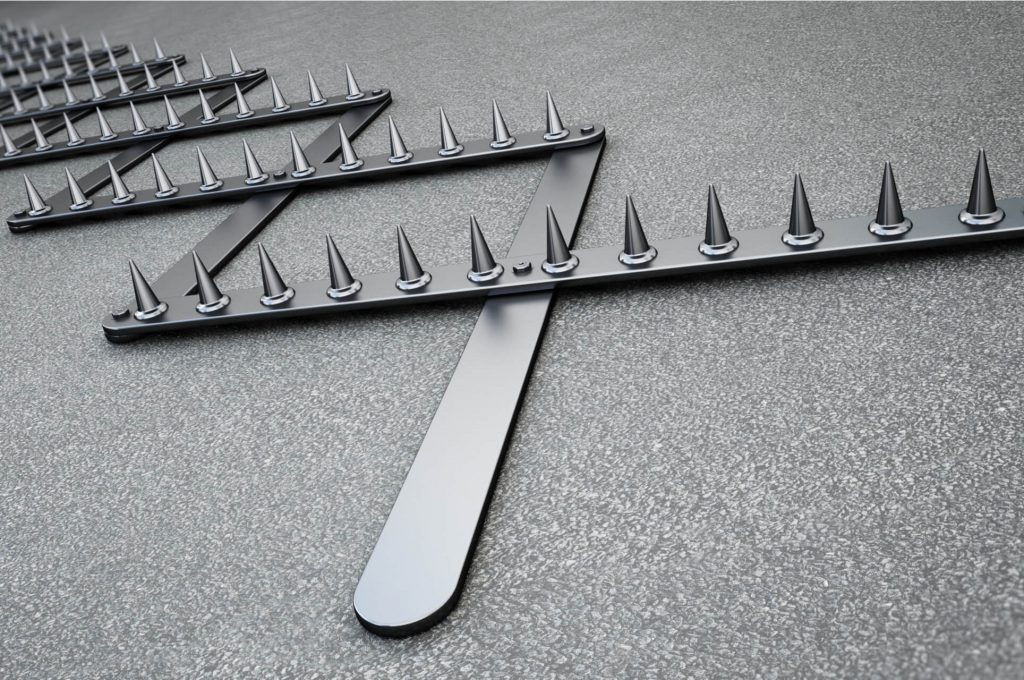

SPIKE STRIPS

The spike strip, used by police to puncture the tires of fleeing vehicles, is a great example of a modern take on an ancient idea. Spike strips are based on caltrops – metal spikes used to lodge in the feet of soldiers or their horses. The first recorded use of caltrops can be charted back as far as 300 B.C.

The modern spike strip was patented in the 1940’s and was a manually deployed device. Prior to this, police could only stop other vehicles by using heavy barriers, which were so slow to deploy that they required prior knowledge of where the vehicle would be. The only alternative was to use police cars to form roadblocks, which had obvious safety implications. The spike strip would puncture the vehicle’s tires in a way that would make them slowly deflate. This causes the vehicle to slow down gradually rather than flip, spin, or crash.

An updated version of the device was developed in 1990 by Donald Kilgrow and design engineer Mel Pedersen. This version is closer to what is in use today, with detachable, hollow metal spikes mounted in a flexible nylon alloy base. This version was still manually deployed; automatically deployed spike strips were then patented in 2006.

BULLETPROOF VESTS

The use of armor predates written history, and people have tried to protect themselves against bullets since the invention of guns. The first recorded attempt at producing a specific ‘bulletproof vest’ dates all the way back to 1538 in Italy. But if we’re talking about modern ballistic body armor then we’re talking about Kevlar.

Kevlar was first discovered by a research scientist named Stephanie Louise Kwolek in 1971. She was working with a liquid crystalline polymer solution that seemed to have some remarkably useful properties. It could be formed into a synthetic fiber, which in turn could be woven and then layered into an incredibly strong fabric. This new fabric was found to have five times the tensile strength of steel. Kwolek was working for DuPont at the time of her discovery, who introduced the product to the world as Kevlar. It immediately caught the attention of the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) who quickly determined that Kevlar body armor could be comfortably worn by American law enforcement officers on a daily basis and that it would save lives.

Kevlar is not the endpoint of ballistic armor, though. Research is still being conducted into “soft solids” or non-Newtonian fluids which are lightweight and flexible at rest but become incredibly resistant under impact. However, for now, Kevlar remains the go-to material for ballistic armor of police forces around the world.

MACE AND PEPPER SPRAY

In 1964 a young female teacher was mugged on the streets of Pittsburgh. The teacher happened to be the colleague of a science teacher named Doris Litman, who was married to Alan Litman, a self-described inventor and holder of several failed patents.

Doris and Alan put their heads together and tried to think of a device that would have protected Doris’ friend. They wanted something that was pocket-sized but that was less dangerous than a gun. After experimenting with a whole range of irritating chemicals and delivery systems they eventually settled on chloroacetophenone, packaged in an aerosol canister that easily sprayed an attacker while keeping the chemical away from the person holding the can. And so, Chemical Mace was born.

Like the TASER, Mace is technically a brand name. Chemical Mace was bought by Smith & Wesson in 1987 and then transferred to Jon E. Goodrich under the name of Mace Security International, the owner of the trademark today. While people still talk about being ‘maced’, the use of chemical mace has fallen from favor and most police today instead carry high concentration pepper spray. Part of this is due to the fact that chemical mace is less effective against people under the influence of drugs or alcohol, while pepper spray remains highly effective.

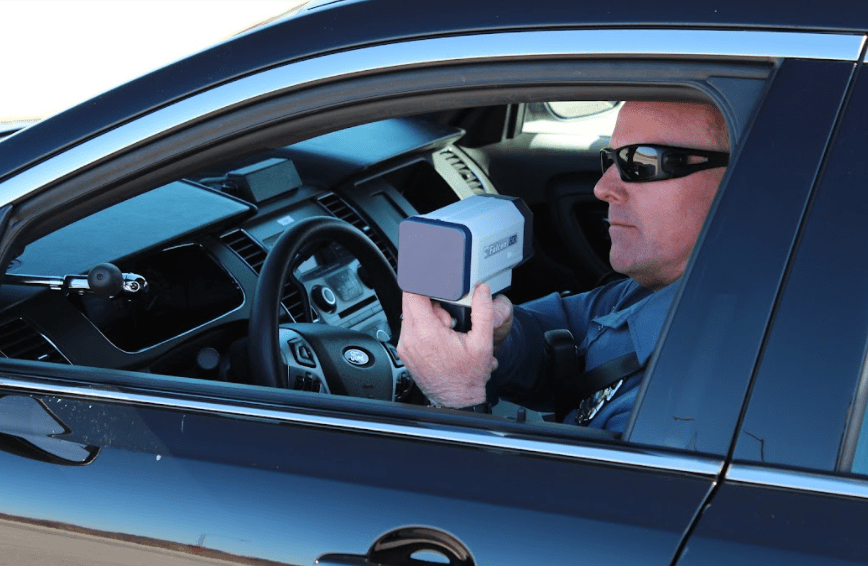

RADAR GUNS

The story of the radar speed gun begins with an aircraft company and design flaw. The Grumman Aircraft Corporation was developing an amphibious aircraft during World War II, which would go on to become the PBY Catalina. Unfortunately for Grumman, the Catalina was damaging its landing gear when coming down on a tarmac runway. They needed a device to measure the sink rate of the aircraft as it came in to land.

John L. Barker Sr., and Ben Midlock were two men who developed radar for the military. They put together a Doppler radar unit from coffee cans soldered shut to make microwave resonators and installed it at the end of the runway, pointed directly upwards. The device worked as intended, measuring the approach of the incoming Catalina.

After the war, Barker and Midlock tested the radar on the Merritt Parkway in Connecticut. In 1947 the device was used by Connecticut State Police for traffic surveys, and New York State started using them in 1948. In 1949 the state police started to issue speeding tickets based on the measurements recorded by the device…and the rest, as they say, is history.